PHNOM PENH, Cambodia — She looks like me, the young woman in the photo. Same roundness of face, same straight black hair that rebelliously flares out at the ends. Like me, her lips downturn slightly at the corners when faced with something serious. She’s clever, I can tell — a spark in the eyes. Her gaze pierces through the display glass into me. She’s tagged with the number 3.

462 has her sleeping baby in her arms. She weeps. 10 is a boy with cherubic cheeks.

It’s a wonder that the Khmer Rouge were so meticulous in documenting the people sent to Security Prison 21 (S-21) when they would simply be starved, horrifically tortured for months until they confessed to something just to end the suffering, then shipped to the killing fields to be executed. The walls of this prison, now the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, are covered with hundreds of stark black and white headshots taken at the moment of arrival. Blindfolds removed, they stood there bewildered, not knowing where they were, what they had done or what was going to happen to them.

S-21 was originally a school before it was converted into a detention centre in 1975. Three-storey buildings face a grassy courtyard where children once played. Visitors can wander the entire complex. As I move in and out of the classrooms that were used as chambers of torture and confinement, one question reels in my head: How? How did this happen?

In 1975, the Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, closed all hospitals, schools and factories, abolished currency and private property, then marched the entire population of Phnom Penh and other cities into the countryside to toil in the fields growing rice. “Brother No. 1” turned back the calendar to Year Zero and set about to engineer his vision of a pure society, an entirely self-sufficient agrarian world run by peasants. Enemies to his fanatical doctrine were dragged to centres like S-21 for interrogation.

The enemies were teachers, doctors, lawyers, nurses. They were monks and nuns. Students — anyone with an education, anyone who spoke a foreign language. Those who wore glasses. Those with soft hands. And as Pol Pot’s paranoia grew during his nearly four-year reign of terror, even members of his own army were purged.

They were all killed, and every member of the person’s family, infant to elderly, was also a threat and had to be killed. To quote Khmer Rouge propaganda: “Better to kill an innocent by mistake then to spare an enemy by mistake.” And “To dig up the grass, one must also dig up the roots.”

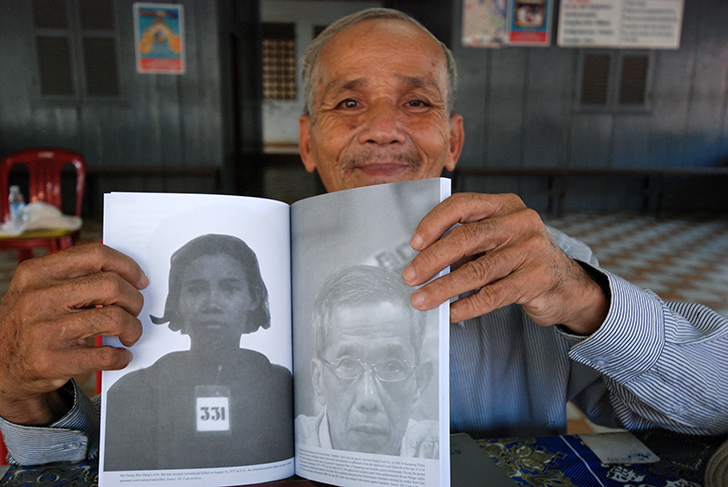

There is another photo of a woman, tagged 331. Bou Meng, 70, sits in the shade in the courtyard holding up the woman’s image for me to see. It is in the book he has written recounting his torture and survival. Between 1975-78, an estimated 20,000 souls were hauled to S-21. Bou Meng is one of only seven known to have survived. An artist, he was spared when he was able to render portraits of Pol Pot. His wife was murdered; the prison photo that he clutches is all that is left of her.

One last photo haunts me. I find it upstairs.

Upstairs, a surprising exhibit. These are the faces of the prison staff, the perpetrators — clerks, cooks, guards — both male and female. In a then-and-now retrospective, the first photo is of when they were Khmer Rouge, impoverished, impressionable youths from the countryside, separated from their families and recruited on the promise of a better life. The second is from 2002, their life and longevity perhaps an insult to the victims.

The photos are accompanied by reflections of what they had done or contributed to. Often they voice a do-or-be-killed scenario, explaining their own state of constant fear.

The photo is of a woman, listed as “Group Leader.” She joined the Khmer Rouge when she was 28 years old — my age. I take a picture of her picture and later, when I look at it, I realize that the glossy surface has captured my reflection. I see my own ghostly image superimposed upon hers.

A visit to S-21 is a must while in Cambodia, not only to learn Cambodian history, but to learn our history — for someone with human hands and a beating heart committed these crimes. If the temples of Angkor Wat reveal the greatest of human ability, S-21 enlightens us to the worst of it.

Select Reading List

Survival in the Killing Fields by Haing S. Ngor

The Killing Fields (film) directed by Roland Joffé

When The War Was Over: Cambodia & The Khmer Rouge Revolution by Elizabeth Becker

First They Killed My Father: A Daughter of Cambodia Remembers by Loung Ung

Pol Pot: Anatomy of a Nightmare by Philip Short

The Years of Zero: Coming of Age Under the Khmer Rouge by Seng Ty

This story was originally published in The Toronto Star, April 2012. At the time, the trials for four senior Khmer Rouge leaders were underway. Last week on August 7th, 2014 – 35 years after nearly 2 million people were murdered – two were convicted of crimes against humanity and sentenced to life in prison. To date, the trials have resulted in just three convictions, at a cost of an estimated US$200 million.