Ten colours, ten stories. This photo essay is the first of a series of posts on the mountainous, ethnically diverse region of northern Laos.

Oudomxay Province, Laos – Two men were sheltered in the cab of a tiny blue flatbed truck while the others, including women and their babies, were huddled around an anemic fire. Laos was well into dry season yet as I got out of my pick-up truck and felt the slow, cold drizzle creep through my fleece – a feeling as welcome as a frigid hand laid on your skin – I became acutely aware of the fact there were different rules to the weather and seasons on the top of mountain ridges. It was another world up here.

My friend and I had stopped in the elbow of the road fat enough to fit our Ford Ranger, partly to admire the spectacular view of the dark peaks swimming in thick grey fog, partly to see what these people were doing roadside out in the rain next to heaps of something hidden under blue tarpaulin. They all seemed to be family and they came to greet us, hands tucked in the pockets of their thin jackets or arms crossed for warmth. They wore flip-flops or no footwear at all.

The tarp protected sacks of corn kernels they had cultivated and harvested on the steep slopes running down from the road. They were waiting for the sale, 2,000 kip or $0.25 per kilogram. They were Hmong, an ethnic minority group still haunted by the history of having sided with the Americans and used by the CIA during the Secret War, only to have the Americans abandon them when they withdrew in 1975. The retribution by the Communist Pathet Lao and Vietnamese Army was terrible.

Hmong are the third largest ethnic group in Laos after the Lao and Khmu, accounting for 6.9% of the population (according to a dated 1995 census). Today, in a developed tourist town such as Luang Prabang, ethnic groups including the Hmong coexist with relative ease, but outside of this bubble, due to chronic malnutrition, lack of medical care and sanitation, isolation, relocation and continued stigma, the situation of some of the Hmong in Laos remains as difficult and precarious as the ridge on which we stood.

We parted, wishing each other a customary “sokdee,” good luck. When we drove off leaving them standing in the rain I was immediately struck with regret and guilt. Why didn’t I think to give them my gloves? My scarf? Why didn’t I bring warm clothes to give away? Surely I could have given them something. I squirmed at the thought. My initial reaction was to pity them, and in pitying them I felt even more uncomfortable for they deserved something better than pity. I was fantasizing about alleviating some of the suffering I projected onto them in this fleeting exchange, perhaps influenced by my own inability to cope with the cold, my own pessimism about the world. They deserved admiration for their tenacity, their independence, their life.

I thought of how the little girl, no more than two, buried her head into her mother’s arms when she saw me and the way her mother smiled and held her close and kissed her cheek.

Sighing, I turned my thoughts to the long road ahead.

Recommended reading:

Tragic Mountains: The Hmong, the Americans, and the Secret Wars for Laos, 1942-1992

The Ravens: Pilots of the Secret War of Laos

The Hmong: A Guide to Traditional Lifestyles (Vanishing Cultures of the World)

I instantly recognized them because of their hair – the distinctive, stylishly twisted topknot fastened with a silver hairpin was traditional Tai Dam. I was driving out of Luang Namtha and it being January, the vast rice paddies flanking the road were withered and browned and I had expected the fields to be deserted yet there they were, busily hauling bushels of long, green feathery plants.

Dry season brings another commodity. The women have collected a type of soft reed from the riverbanks and were now making use of the flat sunbaked lands to lay them out to dry. Once they turned from pale green to ochre to golden brown they could be made into brooms. One kilogram of the dried brush would fetch 3,000 kip or $0.38. It is good money, they say.

I can’t resist trying my hand at the process. I can only imagine what they are thinking as I lift a bundle onto my shoulder – judging by their whoops and cackles, they think it’s hysterical.

The brush is damp from dew and smells sweet and clean, like fresh cut grass on a warm summer day. It isn’t too heavy but the paddy is uneven and I wobble through uneasily like someone who has drunk too much lao-lao whiskey.

“Do they have this in your country?” a woman asks.

No, I think dryly. We go to war with countries over oil so we can produce plastic for cheap plastic brooms that will not biodegrade and will be in the earth for thousands and thousands of years.

HUAY XAI, Bokeo Province – My Frye cowboy boots caused quite a stir in Ban Nam Chang, a Lanten village in Bokeo Province. Perhaps I should have exchanged them for this flashy pink pair of traditional, hand-embroidered Lanten wedding shoes.

33 households live in Ban Nam Chang, only 20 km from the Lao-Thai border town of Huay Xai. Fair Trade Laos have worked with this village to increase the quality of products and the visitor experience. You can visit this village, learn more about Lanten customs and buy from their modest handicraft center.

This Lanten woman is putting the finishing touches on a traditional dress which takes about seven days to complete. The Lanten (also known as the Yao Mun) wear hand-woven dark blue or black naturally-dyed cotton clothing with chemi-dyed pink trim and accents. For black, khaam indigo plant is used with additional plants to make it extremely dark. Each woman has her own secret dye recipes and techniques which she will pass on to her daughters.

Like the majority of tribes who work with cotton, the women in this village grow their own cotton and produce their own cloth. In addition to subsistence farming and making cotton products, embroidery, bamboo paper and charcoal fuel, Ban Nam Chang now grows cassava due demand from the China.

Dry, gin, card, spin, wind, soak, dye – this laborious process transforms puffs of cotton into something that can then be woven into a beautiful textile, into an expression of the weaver’s ethnicity, culture and geography – into a personal expression of the weaver herself.

Cotton (fai) has been grown on a small scale for centuries in Laos and families continue to cultivate plants for their own for personal use. If you think that cotton is always white, think again. Two types of cotton are grown in Laos: white (Gossypium herbaceum) and brown (Gossypium hirsutum). Fed by monsoon rains, it takes eight months until the fluffy fiber is ready to be picked.

The Tai Lue of the Nam Bak District in Luang Prabang Province are famed for their skills with cotton, particularly with dyeing and weaving rich Indigo blue.

MUANG SING, Luang Namtha Province – The old woman unwraps the cloth covering her head, revealing row upon row of heavy silver baubles and coins. She makes minute, meticulous adjustments to her headdress while flashing a toothy smile. Only minutes ago she had been all business trying to sell me Akha handicraft, battling other women in her village in a lively and competitive scrum, a melee of belts and bracelets and embroidered bags. But after the purchases were done, my wallet clearly emptied (she checked), the others drift away and now she’s at ease. Standing beside me she barely reaches my shoulder. It’s clear that age and a near lifetime of seasons have taken its toll. Yet here she is, staunch and proud, allowing me to admire her collection of silver. The many pieces gleam as much as she does at this moment. She stands as if to say, “Look at me. This is me.”

The Akha are found only in the northernmost reaches of Laos and they are a diverse group, with numerous sub-divisions spanning Laos, China, Thailand, Myanmar and Vietnam. For Akha women, silver is part of their identity, silver is part of their everyday being. As I describe in my piece exploring the Akha headdress, the precious metal is prized by the tribe, a clear statement of wealth and status. It is pounded into coins, decorative balls and flowers and these valuable ornaments become heirlooms, passed on from generation to generation. Incredibly these headdresses are traditionally worn year round and everyday, even while working, bathing or sleeping.

Xayaboury Province – When I finally arrived after a five-hour bumpy dusty ride from Luang Prabang, there was a traffic jam. I didn’t need to get out of the truck to see the cause of the backup; an enormous rump filled my windscreen. An elephant was taking a late afternoon stroll down the boulevard. Welcome to the Lao Elephant Festival.

The annual Lao Elephant Festival takes place one weekend in February in Xayaboury Province.* Upwards of 65 domesticated working elephants from all over Northern Laos attend, a sort of conference (where presumably the elephants catch up over some sugar cane, compare trunk sizes then talk politics). It starts as a surreal experience but by the end, you won’t even bat an eyelid at the sight of elephants moseying down the street – except perhaps from all the dust. The festival perfectly captures Lao-style festivities: a local market, a (human) female “Miss Elephant” beauty pageant, Beer Lao, monks blessing the elephants with a baci ceremony and the grand finale parade. The experience doesn’t get more local than this.

The colour of this photo isn’t far off from how everything and everyone looks during hot-dry season (from February to May in Northern Laos). Villages that flank unpaved roads – a common situation in Laos – are the ones who suffer the most.

A single vehicle that passes through kicks up a violent storm that coats everything – every house, every fence, every single leaf – with brown dust, suffocating life. Entire villages transform into terracotta sculptures like Pompeii. Old women sitting in front of their homes cover their faces with cloth while children in the yard stop their play and stand blinking in the sudden blindness before they vanish, consumed. Only the rains can bring relief.

*Never is it more apparent that Laos does not have a standard way to anglicise sounds than with the example of Xayaboury. It is also spelled Sayaboury, Xayabuili, Sainyabuli, Xaignabouli, Sayabouly.

Elephants give themselves dust baths to protect their skin from the sun, to stay cool and keep pests at bay. Visit the Elephant Conservation Center in Sayaboury.

Rainy season. Wet season. Monsoon season. Green season (this is what the travel industry prefers so potential tourists are not put off). Whatever you call it, from June to September the skies in Northern Laos open up almost daily, unleashing a torrent of water that feeds the rice paddies, cleans the air, swells the rivers, fertilizes the banks, floods the roads, agitates the ants and gives birth to a world electric and wholly alive.

Yet “green season” should also be called “brown season” – for where there is rain in Laos, there is mud. Whatever time of year, the roads in Northern Laos leave much to be desired (like, some pavement would be nice). But downpours particularly wreak havoc on the mountain roads. During one memorable trip by van from Luang Prabang to Oudomxay, the normally five-hour journey took more than eight. We encountered washed out roads, sink holes and landslides. Travelling Laos during rainy season is for the adventurous – but this photo of Muang Sing is an example of the heart-stopping scenery that you will be rewarded with.

White cloth universally carries significant meaning across the Tai ethnolinguistic group, which includes Tai Lao, Tai Dam (Black Tai) and Tai Daeng (Red Tai). The dead are wrapped in white cloth in preparation for cremation or burial, and mourners wear white from head to foot. White cloth is not easy to weave, requiring some skill as it will show any imperfection. According to Leedom Lefferts in “The Tai/Thai and the Mekong river” Tai courts often accepted white cloth as taxation in lieu of money.

In a Lao Buddhist funeral procession to the crematory, monks lead the way, followed by nuns (who wear white robes, a stark contrast to the monk’s iconic bright orange robes). Family members, some of whom have taken temporary “vows” as monks or nuns for the mourning period, also dress in white. All are holding onto a ceremonial white cloth as they walk as if drawing the coffin to its final destination.

Hmong, Tai Dam, Yao Mien, Lanten, Akha – all different groups in Northern Laos, all renowned for their embroidery work.

The art of embroidery spans three of the four distinct ethnolinguistic families found in Laos (Hmong-Yao, Sino-Tibetan and Tai-Kadai). The common denominator is skill, time, industriousness, artistry, creativity and patience.

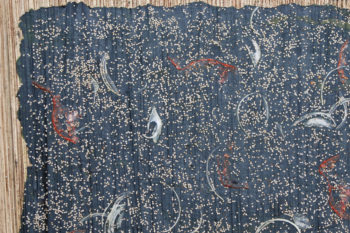

This jaw-dropping work of embroidery was done by Me Èè and Me Tchoupi, Tai Dam women in the town of Muang Sing. Every time I see this photo it reminds me of all the colourful people I’ve met while living in northern Laos. Allow yourself to be drawn into the detail and then it will sink in that every minute vibrant stitch is wholly unique, yet once connected they form patterns that tell a story of a greater narrative.

Recommended reading:

Lao Mien Embroidery: Migration and Change by Ann Yarwood Goldman

All photos and words © Cindy Fan | So Many Miles